Profiles of a Roothbert: Ayize Sabater, ‘96-97

January 13, 2026 | written by Joshua Kurtz ‘22-25, Communications Manager for the Roothbert Fund

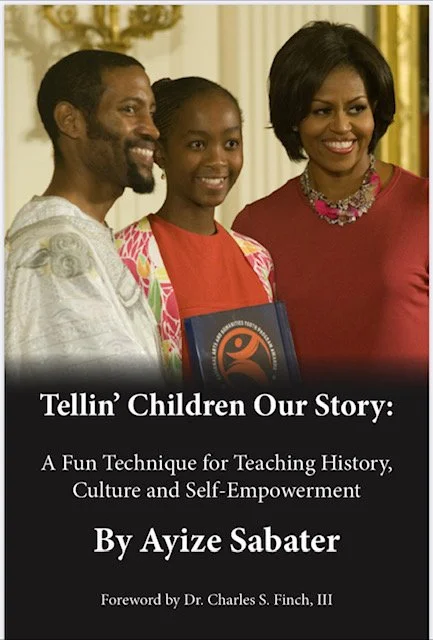

Ayize Sabater (Roothbert Fellow 1996-1997) wears many hats. He is a passionate educator, entrepreneur, author, and champion of inclusive and accessible Montessori education. He is a researcher, public speaker, consultant, and activist. Earlier in his career, he was even a successful restaurateur! In 2010, he received an educational excellence award, presented by Michelle Obama at the White House. He is the co-founder of Montessori for Social Justice and the Black Montessori Educational Fund. He holds a B.A from Morehouse College, an M.Div from Wesley Theological Seminary, and an Ed.D from Morgan State University. He is a husband, a father, and a proud member of the Roothbert community.

I had the opportunity to meet Ayize and his children in June, 2025 during a Pendle Hill retreat that centered around grief and storytelling. Immediately, I was drawn to his bright smile, infectious laughter, and uncanny ability to make everyone in the room – friends and strangers alike – feel welcome.

Ayize and his family have been attending Pendle Hill retreats for decades. “We’ve made it a regular part of our vacations,” he told me. “The Roothbert Fund has been a tremendous cornerstone of our family’s development.”

A few months later, I had the chance to interview Ayize about his upbringing, his career, his spiritual and political ancestors, and his unwavering commitment to social change.

+++

Ayize grew up in East Flatbush, Brooklyn in a poor, working class, single-parent household. As the oldest child, Ayize was responsible for caring for both his siblings and his mother, who wrestled with mental health challenges throughout her life. Though Ayize has fond memories of his childhood, it was difficult. “My mom was no slouch,” he told me. “She didn't spare the rod to spoil the child, to say the least.”

While attending Midwood High School at Brooklyn College, Ayize struggled to find his path. “To try and be in the cool crowd, I would act the fool,” he shared. “At some point I figured out that I needed to walk a very fine line of doing well enough that my mom wouldn’t take the belt to my behind, but not so well that the boys would beat me up for being a nerd.”

This shifted when Ayize met Grace Garofolo, a history teacher who quickly took an interest in him and his academic success. “I must have handed in a paper that was really good,” Ayize recounted. “She said, ‘You’re actually pretty smart! If you keep handing in these crappy papers, I’ll tell your mom!” So, to avoid his mom taking a belt to his behind, Ayize began to apply himself to school. When senior year came along, Ms. Garofolo encouraged him to consider applying to Morehouse College, a historically Black men’s college in Atlanta whose graduates include Martin Luther King, Spike Lee, and Howard Thurman.

At first, Ayize scoffed at the idea. Most graduates from his high school went on to attend city or state schools in NY, and Ayize had already received an acceptance package from SUNY Buffalo. Besides, it was already spring of his senior year, and the deadline to apply had long passed. Still, Ms. Garofolo encouraged him to visit, and soon Ayize and a friend found themselves “on the midnight train to Georgia.”

When Ayize arrived, he almost immediately fell in love with the environment. “The grass was green, the birds were chirping, the bees were buzzing.” But it was his experience visiting Spelman, the all women historically Black college next door, that convinced him to send in an application. “Despite the surroundings,” he told me, it was “the sisters, the beautiful Black women, that sealed the deal for me to seek to attend Morehouse.’”

+++

At Morehouse, Ayize had the opportunity to discern his vocation. When he first arrived, all he wanted was to become a successful entrepreneur. He became an accounting major, but soon found himself bored by the tedious accounting routine. A professor in the department, Dr. Willis “Butch” Sheftall, encouraged him to study something that he actually cared about. Ayize enjoyed the subject of history, so he met with the chair of the history department, Dr. Alton Hornsby, a renowned historian, author, and editor of the Journal of Negro History. Inspired by Dr. Hornsby’s work, Ayize switched his major to history.

Ayize’s experiences at Morehouse, as well as the community he built there, set the stage not only for his career, but also for his spiritual development. While working as a volunteer with the Morehouse Male Mentoring Program, Ayize discovered just how transformative education could be. “Forget trying to be an entrepreneur,” he told himself. “We need to work on saving the children.”

During his senior year, Ayize and several of his close friends decided to build a school that would be “open to all and oriented to the needs of African-American children,” as one reporter wrote in The New York Times. In September 1992, just a few months after graduation, Ayize and his partners opened their first school, named Freeform Academy, in Atlanta. His friends handled the business while he served as the principal, responsible for everything from cleaning toilets and driving buses to teaching classes.

Though Ayize had shifted his focus away from business, he and his friends never lost their interest in entrepreneurship. The group wasn’t satisfied with opening merely one school. In fact, Ayize’s business partner set a goal to open 1,500 schools by the year 2000! It was an ambitious goal, even a preposterous one, but it was rooted in the urgency of the moment. “Who’s thinking about education for the Black child?” Ayize and his colleagues asked themselves. “We have to do it.”

The group’s entrepreneurial spirit extended beyond their commitment to education. At Morehouse, Ayize and many of his friends were vegetarians. Given the cafeteria’s notoriously terrible food, Ayize and his friends often cooked for the community. So it was only natural that, at some point, they would open a restaurant.

In early 1993, just a few months after they launched Freeform Academy, Ayize and his friends opened Delights of the Garden, a vegetarian restaurant that specialized in raw, affordable food. The restaurant quickly took off, and soon the group set a goal of opening 1,000 branches by the year 2,000. They even wrote a cookbook, entitled The Joy of Not Cooking. One reporter wrote in The New York Times, “A look at the Delights of the Garden menu shows what many vegetarians already know: vegetarian doesn’t have to mean boring.” By 1995, the group had opened five restaurants – 2 in Atlanta, 2 in Washington, D.C., and 1 in Cleveland – and they were working on opening several more in New York City and Florida.

Freeform Academy’s progress, on the other hand, was slower. While the school had grown from 12 to 120 students, by 1995 Ayize and his partners hadn’t yet opened their second school. “In our mind it was failing,” Ayize told me. So he moved to Washington, D.C., where he launched a new school, helped to keep the Howard University branch of Delights of the Garden afloat, and built a family.

+++

Ayize was first introduced to Montessori education by his roommate at Morehouse, who would later become his business partner, Imar Hutchins. “He was one of the smartest of the smart,” Ayize told me. “This cat would barely crack a book open, while I stayed up till 2 or 3 in the morning studying.” Eventually, Ayize asked Imar how he did it. “I don’t know, I’m a Montessori child,” Imar responded.

Though the first school that Ayize opened in Atlanta was inspired by Montessori education, it wasn’t until years later, while Ayize was living in D.C. with his wife and five children, that he would immerse himself in the history and pedagogy of the Montessori movement. At that point in his career, Ayize was running a successful afterschool program where he worked with older teenage students, and one day the parents of a student suggested that he open a full day school. He was hesitant, so he turned to his wife, a Montessori teacher, to build that school.

Ayize recounts that while Imar introduced him to Montessori, it was his son who ultimately convinced him of the power of Montessori pedagogy. Ayize remembers visiting his youngest son, 7 years old at the time, at school. Ayize was blown away by what he saw. “The stuff that this 7 year old was doing surpassed what the 14, 15, and 16 year olds in my afterschool program were doing!” he exclaimed. He then realized that “Montessori is the way to transform the world.”

Some background on Montessori education: Founded in the early 20th century by Italian physician Maria Montessori, the Montessori method centers around children’s interests, rather than formal teaching methods. “It’s common sense education,” Ayize shared. Rather than forcing children to study a particular arbitrary curriculum, Montessori teachers allow students to pursue their own passions. Ayize’s son, for example, fell in love with Greco-Roman culture and, by the age of 7, became somewhat of an expert. Moreover, Montessori schools encourage older students to teach younger ones, fostering a type of community that is rarely seen in traditional educational settings.

“Montessori education, simply put… It’s common sense to allow children to be free and independent in their environment – to move, to laugh, to sing. They’re actually having fun while learning” Ayize shared. Whereas kids in traditional environments often dislike school, many Montessori children find joy in learning. “You have to put the child in the driver’s seat for their own learning,” Ayize affirmed.

However, as his career progressed – and as he spent less time in the classroom and more time with school administration, raising money, applying for grants, and spreading the word about the Montessori method – Ayize realized that, in this day and age, Montessori education is still obscure and inaccessible to many communities.

Maria Montessori opened her first school for poor children in Italy – children who had been deemed “uneducable” by the state. She soon received international acclaim, as word spread about her successful, scientifically-based pedagogy that promoted human development. However, Montessori education garnered the attention of elite communities, who gradually co-opted the method for themselves. As time went on, Montessori schools were often relegated to “wealthy, well-to-do, white folk.”

In 2013, Ayize co-founded Montessori for Social Justice (MSJ), which is dedicated to dismantling systems of oppression and amplifying the voices of the global majority. Ayize’s early work with MSJ centered around shifting the language that people use when they talk about social change. Rather than referring to marginalized communities as “minorities,” the organization emphasized that people of color actually make up the majority of the world, and should thus be referred to as “people of the global majority.” Relatedly, Ayize rejected the language of “charity” in his work with the organization. “This is not just window-dressing,” he told me. “This is the core essence of trying to save humanity.”

Over the past several decades, Ayize has devoted himself to returning Montessori to its roots. The driving question behind much of his work is: How can we make Montessori education more accessible? “We still haven’t cracked that nut,” he told me. A few years ago, he co-founded an organization called the Black Montessori Education Fund (BMEF), which is raising money to make Montessori education accessible to the Black community.

In recent months, Ayize has worked tirelessly to spread awareness of the crises in education as reported in the2024 Nation’s Report Card, which indicates that students around the country are struggling with basic skills. For example, the study found that 70% of Black 12th graders are below basic in math performance, an increase of 6% since 2015. Ayize is quick to highlight, though, that children of all ethnicities, races, and backgrounds with the exception of Asian/Pacific Islanders, are doing poorly. “This appears to be a race to the bottom,” he shared. “Who is sounding the alarm? Our educational house is on fire. This educational joint is going to burn down if someone doesn’t do something.”

+++

For Ayize, this work is deeply spiritual. Although his mom made him and his siblings go to church throughout their childhoods, Ayize wasn’t interested in religion until he went to Morehouse. There, he joined an African-American fraternity. While participating in a rite-of-passage process, he had something of an epiphany. He came to understand that “it is by the grace of God that we’ve come this far. If we’re really looking to be transformative agents in the world, then we have to move with the spirit of God to transform to darkness before us, to cast it out, by shining God’s light. It was there, at Morehouse, where I put my spiritual anchor down.”

Years later – driven by the conviction that “to make change in society, we need to immerse ourselves both in the word of God and also in the rule of law” – Ayize pursued a Master of Divinity degree from Wesley Theological Seminary. In order to pay for school, he applied for a fellowship from the Roothbert Fund.

+++

In moments of despair or hopelessness, Ayize turns to all the activists, educators, and spiritual leaders who came before him. “I’m a student of history,” he said. “When I’m feeling down, looking at the lessons of these ordinary people who were able to achieve the extraordinary fires me up.” Ayize cites figures like Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Howard Thurman, Malcolm X – and, of course, Maria Montessori. And the historical inspiration of these luminaries moved Ayize to write a book, where he shared some of the “secret sauce” which helped his organization win a White House award.

“I’m going to try to take the water I have and spread it on these seeds so that we can transform what’s happening right before our eyes,” he shared. “I believe that Montessori pedagogy is one of those seeds of hope that when implemented with fidelity and love, can potentially change the world. And that’s why I’m fired up to bring Montessori education to more Black children, more Black families, more Black communities."

At the end of our conversation, I asked Ayize what wisdom he’d like to share with current Roothbert Fellows. “Keep hope alive,” he offered. “Another world is possible.”